Future of Energy: Efficiency

This story is part of a series on Stanford collaborations helping to create the Future of Energy.

This story is part of a series on Stanford collaborations helping to create the Future of Energy.

In the past few decades, improvements in energy efficiency in our homes, buildings and cars have significantly reduced carbon emissions by cutting demand. In addition to the environmental impacts, this enhanced efficiency has improved national security, reducing energy imports four times as much as the combined increases in domestic production of all energy sources combined.

Continuing that trend of increasing efficiency has been the focus of the Precourt Energy Efficiency Center (PEEC), which emphasizes efficiency in buildings and homes – like more efficient heating, cooling and lighting – as well as transportation, green computing and how people make energy decisions in their daily lives.

Buildings

Yi Cui, a professor of materials science and engineering who works on energy efficiency as well as improved batteries, said he started thinking about heating and cooling when looked at where most energy goes.

“We spend 30 percent of electricity to cool and heat the building, which is about 13 percent of the total energy consumption,” he said. “The estimation is, if you can change the set point of air conditioning by 1 degree Celsius, you save 10 percent of energy use in the building heating and cooling.”

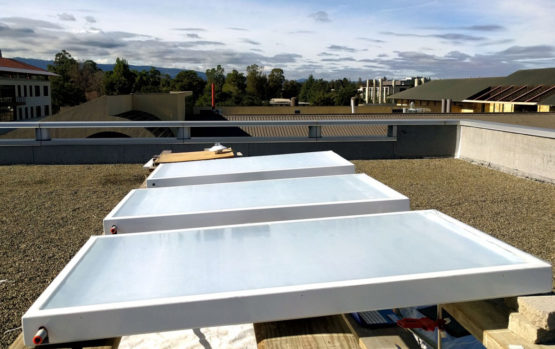

A team led by Shanhui Fan has developed a rooftop device that reflects heat from the sun back into space rather than letting it be absorbed by the building. The group recently showed that it could cool water for air conditioning without electricity, and calculated that on a hot day it could save as much as 21 percent on energy to cool the building. Another group has developed a window that quickly transitions between clear and dark to block heat on sunny days.

Inspired by the cost of cooling buildings, Cui wondered if he could cool people instead. He and his group developed an opaque fabric that allows body heat to pass through. People wearing cooling clothing made from this material would require less energy spent on air conditioning.

PEEC Director James Sweeney’s 2016 book, Energy Efficiency: Building a Clean, Secure Economy, describes how America has drastically changed the way it uses energy beginning with the 1973 oil embargo.

Transportation

Fossil fuels carry a lot of energy at low weight and are fast and easy to refill – qualities that make them ideal for transportation.

“It only takes two and a half to three minutes to completely fill your tank,” said chemical engineer Thomas Jaramillo, who is working on alternative sources of fuels. “Let’s say you plug in your phone for three minutes, what can you really do with that energy?”

Transitioning away from fossil fuels will require batteries or hydrogen fuel cells that are as convenient as traditional energy sources and that are as easy to recharge. To that end, several groups are working toward lighter weight batteries, and Shanhui Fan and his students have developed a wireless technology for recharging those batteries on the go. In the near term, their work could improve charging of smaller devices, but they also envision wireless devices along roads to charge passing electric cars.

Other faculty are developing more efficient hydrogen fuel cells and lightweight solar panels for recharging car batteries or creating hydrogen fuels.

Leave a Reply