Liquid Fuel That Can Store The Sun’s Energy For Up to 18 Years

Originally Published at www.sciencealert.com

Researchers have invented a liquid isomer that can store and release solar energy.

Researchers have invented a liquid isomer that can store and release solar energy.

No matter how abundant or renewable, solar power has a thorn in its side. There is still no cheap and efficient long-term storage for the energy that it generates.

The solar industry has been snagged on this branch for a while, but in the past year alone, a series of four papers has ushered in an intriguing new solution.

Scientists in Sweden have developed a specialised fluid, called a solar thermal fuel, that can store energy from the sun for well over a decade.

“A solar thermal fuel is like a rechargeable battery, but instead of electricity, you put sunlight in and get heat out, triggered on demand,” Jeffrey Grossman, an engineer works with these materials at MIT explained to NBC News.

The fluid is actually a molecule in liquid form that scientists from Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden have been working on improving for over a year.

This molecule is composed of carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen, and when it is hit by sunlight, it does something unusual: the bonds between its atoms are rearranged and it turns into an energised new version of itself, called an isomer.

Like prey caught in a trap, energy from the sun is thus captured between the isomer’s strong chemical bonds, and it stays there even when the molecule cools down to room temperature.

When the energy is needed – say at nighttime, or during winter – the fluid is simply drawn through a catalyst that returns the molecule to its original form, releasing energy in the form of heat.

“The energy in this isomer can now be stored for up to 18 years,” says one of the team, nanomaterials scientist Kasper Moth-Poulsen from Chalmers University.

“And when we come to extract the energy and use it, we get a warmth increase which is greater than we dared hope for.”

A prototype of the energy system, placed on the roof of a university building, has put the new fluid to the test, and according to the researchers, the results have caught the attention of numerous investors.

The renewable, emissions-free energy device is made up of a concave reflector with a pipe in the centre, which tracks the Sun like a sort-of satellite dish.

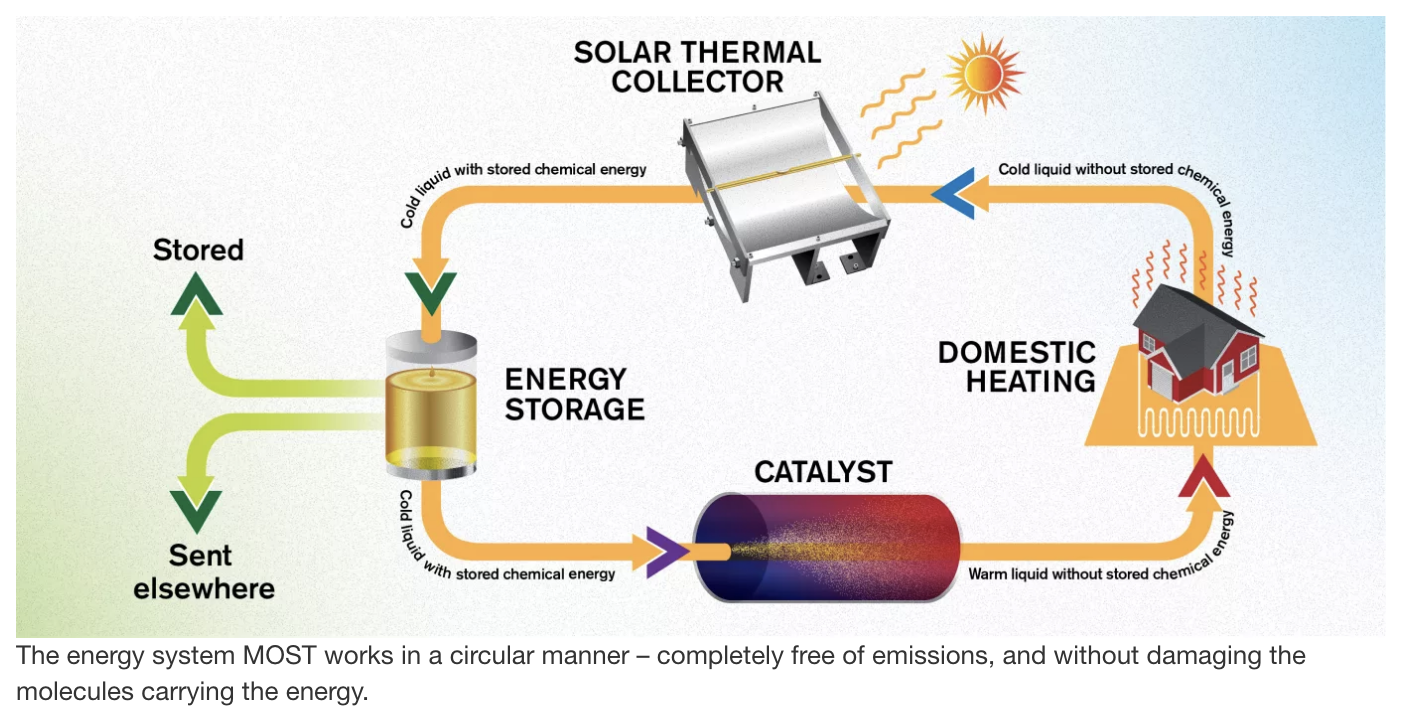

The system works in a circular manner. Pumping through transparent tubes, the fluid is heated up by the sunlight, turning the molecule norbornadiene into its heat-trapping isomer, quadricyclane. The fluid is then stored at room temperature with minimal energy loss.

When the energy is needed, the fluid is filtered through a special catalyst that converts the molecules back to their original form, warming the liquid by 63 degrees Celsius (113 degrees Fahrenheit).

The hope is that this warmth can be used for domestic heating systems, powering a building’s water heater, dishwasher, clothes dryer and much more, before heading back to the roof once again.

The researchers have put the fluid through this cycle more than 125 times, picking up heat and dropping it off without significant damage to the molecule.

“We have made many crucial advances recently, and today we have an emissions-free energy system which works all year around,” says Moth-Poulsen.

After a series of rapid developments, the researchers claim their fluid can now hold 250 watt-hours of energy per kilogram, which is double the the energy capacity of Tesla’s Powerwall batteries, according to the NBC.

But there’s still plenty of room for improvement. With the right manipulations, the researchers think they can get even more heat out of this system, at least 110 degrees Celsius (230 degrees Fahrenheit) more.

“There is a lot left to do. We have just got the system to work. Now we need to ensure everything is optimally designed,” says Moth-Poulsen.

If all goes as planned, Moth-Poulsen thinks the technology could be available for commercial use within 10 years.

The most recent study in the series has been published in Energy & Environmental Science.

Leave a Reply